Just past the media and the mouths of fans' fixture that was the tragi-comical penalty kill - vacuuming up the attention of both pitchfork-equipped corps of the Orange Crush and the chuckles of visiting broadcasters - what went miraculously much less noticed was a squandering of the man-advantage.

This was, in part, due to a puzzling lack of opportunities. In a setting where the go-to defending tactic against Connor McDavid was supposedly being cracked down upon and the preseason filled with penalties for the slashes to the hands at a rate that indicated the league was saying this was the new now in both actions and words, the overall penalty-drawing rate of the league did not increase and the Oilers ended up spending 34 minutes less on the powerplay than the year before. In a bewildering development, McDavid himself drew 12 less penalties at 5v5 year over year, despite playing more and being undeniably more dangerous. Those lost 12 whistles figures for a thirty-two percent drop in rate of penalties drawn during 5v5 play, jarring and confounding against the previously mentioned backdrop of cracking down on obstruction.

But after taking this into consideration by looking at the rate at which the Oilers scored in the time they were given, we find that the team was the least effective in the league at scoring goals during 5-on-4 play.

This is a drop from 6th in the league in 2016-17. This figures out for is a drop in goal differential from +46 to +25.

Comparing the impact of this to the more infamous penalty killing, one also has to add in the in-season trending of both. From the first game of the season through to Christmas, the Oilers lead the league in 4-on-5 goals against per hour with 10.10. To end of the year from there, they were 16th in the league with 7.14 per hour. If you shrink that second side performance to the last 25 games, they allowed the second lowest at 3.21.

Let's contrast this with the 5-on-4 performance, by the exact same measures:

In the chosen first frame, their rate was 8th-lowest at 5.70.

In the chosen second, it drops to NHL-worst with 4.59.

Shrinking the sample to the last 25 raises it to 5.53, still worse than the pre-Christmas rate.

With the penalty kill, there's a lot you can point to for improvement. A change in personnel via players leaving at the deadline, and a change in tactics via Todd McLellan taking over the structuring from assistant Jim Johnson gives real, concrete reasons to believe that the change is more than just the good side of variance and goaltending.

Said assistant was also let go of by the organisation shortly following the close of the regular season.

It gives you a grounded belief that such failure is unlikely to be in the cards for next season.

But the powerplay is the opposite, and that's why I think it should be talked about more. The personnel is returning, there appeared to be no recourse for its floundering, and the man in charge of the unit is now coaching the AHL affiliate.

When Jim Johnson was relieved of the penalty kill, and Todd McLellan took over and implemented a basic structure, the problem was solved.

So then, in this event that there's new assistant coaches, you can simply say that if the penalty kill fails again, you can take the duties away from the assistants, give them to McLellan, and live happily ever after.

But by the same logic, there's no aiding a failing powerplay in the future. Yes, there is new assistants. Yes, Emmanuel Viveiros was a fine candidate and I'm glad they have him, but what we're talking about here is 'Plan B'.

They got to Plan Z at some point on the 5-on-4 last year, when they quite literally just rolled the 5v5 lines out there, which is somewhere between taking your toys and going home and saying that you're not even really trying, bro.

This makes performing the dissection of the powerplay infinitely intriguing in comparison.

Random Number Generating

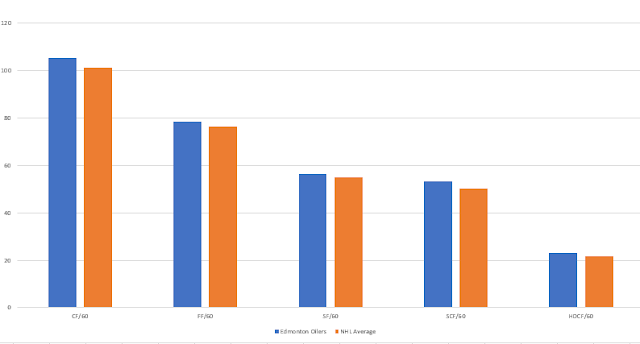

Let's check out the type of shots and chances recorded by the Oilers to contextualise the goals.

(By the way, those following unless denoted otherwise and all those before this notice are via NaturalStatTrick.com)

Everything looks fine and dandy here, from a generation perspective the Oilers were above league average, but personally when I look at stuff like this on the powerplay what these rates tell me is more that the team was fine in transition - gaining the zone and setting up - rather than they were actually good at setting up real chances. This type of shot type/location context is useful in larger samples during 5v5 play, but in 5v4 the context is so wildly different team to team based on personnel and tactics that really, no two shots are the same.

For example, Patrick Laine:

Laine's recorded as registering a total 14 high danger chances on the powerplay in his first two years of NHL play. He's scored 29 goals. You can see where these shots come from, betraying distance they're dangerous because of the amount of right-shot one-time options the play has coming off of the right half-wall on WPG's powerplay:

So these are far-out shots from Laine that will result in a repeatable overperformance of shot location averages because of both his shot and the tactical depth of the unit he's on.

Now that we've established that you earn your shooting percentage much more at 5-on-4 than 5-on-5, let's look at how the Oilers executed:

And there it is. The overall shooting % looks bad by the bar, but I'll add the information that 9.09% was good for worst in the NHL - two teams shot better 5-on-5 than the Oilers did 5-on-4, and eight teams shot better even strength overall than Edmonton did 5-on-4.

These are remarkable statistics, let's check out who made up this average player-by-player

- In 2017-18, 210 forwards played more than 100 minutes of 5-on-4 time,

- The average of their shooting percentage was 14.81.

- 1st on the team was Ryan Nugent-Hopkins; 70th/210; 18.18 SH%.

- 2nd on the team was Leon Draisaitl; 103rd/210; 15.00 SH%.

- 3rd on the team was Connor McDavid; 107th/210; 14.71 SH%.

- 4th on the team was Milan Lucic; 118th/210; 13.04 SH%.

- 5th on the team was Ryan Strome, 175th/210; 6.9 SH%.

- 6th on the team was Mark Letestu, 179th/210; 6.45 SH%

- 7th on the team was Patrick Maroon, 182nd/210, 6.25 SH%.

I'd like to address two relevant things as they've just come back to me. First, often when the Oilers' season was talked about in real-time, it was remarked that this is basically the same team as 2016-17.

At 5-on-5 and 4-on-5 this was obviously not true, but the Venn diagram of people who said this and the people who underrated players like Jordan Eberle, Tyler Pitlick, Benoit Pouliot, David Desharnais and Brandon Davidson would be a circle, so they could simply just mention their evaluation of those players as entirely dispensable, and continue on with their premise.

But on the powerplay, that sentiment holds much more true. This absolutely was an almost fully returning cast failing to deliver the same goods from the year before. Let's repeat the exercise for them.

- In 2016-17. 200 forwards played more than 100 minutes on 5-0-4 time,

- The average of their shooting percentage was 15.63.

- 1st on the team was Milan Lucic, 25th/200; 25.00 SH%

- 2nd on the team was Leon Draisaitl, 47th/200, 21.28 SH%

- 3rd on the team was Ryan Nugent-Hopkins, 59th/200, 19.23 SH%.

- 4th on the team was Mark Letestu, 72nd/200, 17.95 SH%.

- 5th on the team was Patrick Maroon, 151st/200, 10.00 SH%.

- 6th on the team was Connor McDavid, 156th/200, 10.00 SH%.

- 7th on the team was Jordan Eberle, 161th/200, 8.82 SH%.

This is stark. The team had four top-half guys the year before, just barely two this past one. Only Ryan Nugent-Hopkins and Connor McDavid improved. Which, by the way, was the 2nd thing I wanted to mention that was talked about - multiple times I heard one of the problems with McDavid's powerplay unit was he 'wasn't a threat to shoot'. This is demonstrably false, he shot more and more potently year over year. We see the SH% increase, I'll also tell you now he shot more than he did the year before too. If he wasn't a threat to shoot in 17-18, then he also wasn't in 16-17 and that unit ran well, so it's evidently very low on the list of problems compared to how much it was talked about. I remember hearing it more than any other criticism of the team's powerplay by the media and fans, Oilers or otherwise.

Let's look at some of the big drop-offs:

Typically the ordering of a particular piece of discourse with regards to shooters shooting or players playing goes like this: Someone notes a players' high shooting percentage or point production rate, and says the player should shoot more, or the coaching sraff should play him more. A second someone will retort that if they shot more, their percentage would go down, and if they played more(harder) minutes, their production rate would go down.

The second someone is right quite often, there. The less you shoot the more often you're shooting in dangerous situations is the theory, and it plays out like that in practice a lot as well. The holders of the highest shooting percentage are often playmakers, who will look and look for someone to dish it to and have to have a very potent opportunity in front of them to convince them to shoot it themselves.

Here though, bafflingly, we see the opposite. Half the shot rate, and half the shooting percentage. That's how you go from 3.39 goals/60 to 1.06/60. It's such a cataclysmic shift that it suggests not a failure to perform a role, but a switch in role entirely. With that in our pocket, let's move to the shot map.

First thing to note - the total time on ice. We're looking at just raw counts, here, with a sizeable difference in amount of time to accrue them. For the answer to that question, you can refer back to the chart, where it shows Milan did indeed get much less chances at finishing from tips and deflections some feet out. The role change isn't clear from here, all we've been told is that the spots he's to shoot from stayed the same. What we do know from these two pictures is that the play went through Lucic less, there was a lower rate of executing net-front stuff-in and tip-in attempts. Is this from execution solely, or did they just try it less?

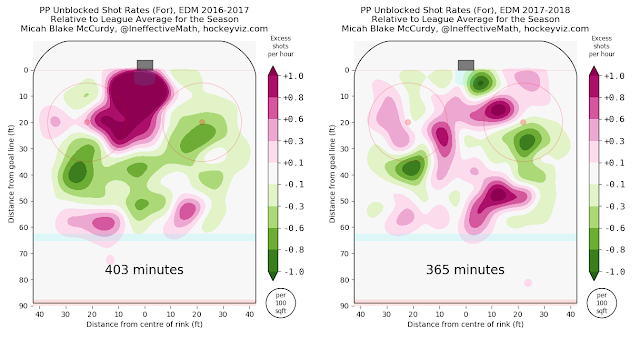

Everything that applied to Milan applies here too. This one we know was a role change. It's a very alarming phenomenon to learn this about these two players. 49 goals were scored 5-on-4 by forwards on Edmonton the year before last, these two players scored 22 of them. They were the primary options in close on a powerplay that looked like this:

Yeah. Good times. I remember watching this team draw a penalty while trailing and cackling as 97 came off the half wall and found 29 who found 27 who scored. Letestu's work at the right circle got more press(likely due to the novelty) but he scored just seven goals to the ten and twelve of the big netside men.

Aside from that aside, let's look at Leon's individual picture.

And does this ever match my eye, and memory.

This looks like a guy who went from having a job to having a dozen hats because folks are quitting the company. Notice especially that sparsity of the goals in 17-18 compared to the closely packed red marks of the year before. There's also much more similar TOI totals between the years compared to our look at Lucic's, which helps looking at the raw dots be a more fair method. But, I think a density chart would help communicate the total shot attempt disparity more.

Yeah, this is the result of moving a player around. What we'll have to look for in the video is what exactly preceded this - was the go-to play getting shut down too much, and a scramble followed after 'Plan A' didn't work? Or, did they come out the gate with a different setup than last year (likely) that saw Leon in different spots? Two places I'll draw your attention to is the top-side of both circles. There's a bunch of wristers on the left, what was the play there, looking for a rebound, or a low slot tip? Also, it looks like there's slapshots on his off-side circle, that's a royal road pass play, when during the year were they trying that, was that what they came into the season with, or was it when they plugged Strome onto the top unit later and had him make those cross-ice feeds? Tons of questions to consult the video with.

This is an equal drop in performance, but with a less confounding immediate observation; we have a distance problem.

Letestu's play eroded enormously in one summer, but that was due to his boots, not his shot. He actually shot better at 5-on-5 in last year's campaign than the once preceding, what he didn't lose was his shot. We've got something to look for in our spray chart, and something to look for in the video - shot type and distance and pre-shot puck movement, respectively.

A much simpler problem to solve is represented here, to be sure.

Letestu's play eroded enormously in one summer, but that was due to his boots, not his shot. He actually shot better at 5-on-5 in last year's campaign than the once preceding, what he didn't lose was his shot. We've got something to look for in our spray chart, and something to look for in the video - shot type and distance and pre-shot puck movement, respectively.

A much simpler problem to solve is represented here, to be sure.

Given a 22% drop in total minutes, the density chart is key here for contextualising the location.

But what this one is particularly good for, is the exact types. Look at the amount of misses especially in 16-17. This speaks to a willingness to go to that cross-ice play over and over. This is a curio that drew me to check the numbers on it, and I found that Letestu went from about 30 shot attempts per hour to about 23. They just weren't running that play as often - one could say that perhaps the passes were being broken up repeatedly, or missing, but that would likely show up in the possession stats as it's hard to retain possession if a hard, cross-ice pass going to a side of the ice with only one player misses. Still though, we ought to find out in the video. The shot distance thing, especially clear in the area between the crease and the right dot is particularly barren by looking just at these raw attempts is troubling, but again we'll have to help our eyes with the density version.

As expected we see a bit less of a wholesale shift in location, but what should be noticed is those three pockets right dot and up - a lot of these are slapshot-squares and point to more cross-ice passes being made for shots at distance, of which an 11% accuracy drop can inform its effectiveness.But what this one is particularly good for, is the exact types. Look at the amount of misses especially in 16-17. This speaks to a willingness to go to that cross-ice play over and over. This is a curio that drew me to check the numbers on it, and I found that Letestu went from about 30 shot attempts per hour to about 23. They just weren't running that play as often - one could say that perhaps the passes were being broken up repeatedly, or missing, but that would likely show up in the possession stats as it's hard to retain possession if a hard, cross-ice pass going to a side of the ice with only one player misses. Still though, we ought to find out in the video. The shot distance thing, especially clear in the area between the crease and the right dot is particularly barren by looking just at these raw attempts is troubling, but again we'll have to help our eyes with the density version.

You can also see the amount of bumper-spot activity here was substantial - another video cue. Notice also that for all of the general activity up high, none of them resulted in first-shot goals. This is an awful result, but only if we can also rule out low rebounds, which the bumper player can often produce.

In checking for this, I've found that Letestu's rebounds created dropped from 1.80/60 to 0.93/60, and his primary assist per hour rate dropped from 1.08 to 0.46.

So, all in all, from the data we've gathered it certainly looks like when Letestu's role did change, it was almost entirely ineffective at generating goals and dangerous chances.

These three forwards - Mark Letestu, Milan Lucic, and Leon Draisaitl - accounted for 29 of the 51 goals scored by the top-5 converting 5-on-4 unit of 2016-17. All of them appeared to have significant changes in duties, and all of them dropped their goal-scoring by significant amount, combining for just 11 goals in 2017-18. (Though, it should be noted Letestu only played 60 games with the club last year before leaving in a deadline deal to Columbus.)

We will look at McDavid in video of course, but in terms of finishing the forwards I've featured in the data are by far the most important: In 2016-17, the other 17 goals scored by forwards were split among 6 other players including 5 from the 2nd unit's mastermind, Ryan Nugent-Hopkins.

The Defenders

Another large shift in the end-game of the Oilers powerplay is that they let many more plays go by shooting from the point.

In 2016-17, Andrei Sekera and Oscar Klefbom combined for 362 5-on-4 minutes of the 388 made available to the team.

On the first powerplay unit with Connor McDavid, Sekera clocked 10.23 SOG per hour, and 21.03 shot attempts per hour.

Oscar Klefbom in the same situation registered 9.06 SOG per hour, and 24.67 shot attempts per hour.

In 2017-18, the team had 351 such minutes, but with Sekera gone, the non-Klefbom minutes were divided amongst a number of blueliners. 63 to Matt Benning, 38 to Darnell Nurse, 35 to Andre Sekera, 31 to Ethan Bear, 17 to Kris Russell, and most perplexingly of all: 13 to Yohann Auvitu.

The ones we're (mostly, for now) examining are the top unit ones, and those belonged to Klefbom and nobody else of significant sample.

And in these minutes, Oscar Klefbom's SOG rate rocketed up to 16.67 per hour, and 33.31 shot attempts per hour.

That shots-on-goal rate ranked 6th among defencemen league-wide who played at least 100 minutes 5-on-4. He also sported the lowest shooting percentage until Keith Yandle's 0(zero!) at the 21st highest shot rate.

Put another way, this was funneling an inordinate amount of your possession value, your shot attempts through a defenceman with a shoulder injury who just isn't hitting it.

We know this is a development that certainly wasn't discouraged as during an interview before the 2017-18 season Oscar Klefbom mentioned that he and Jim Johnson had talked about "having a mindset and a goal to just shoot as much as I can".

Not entirely ineffective was the rebound-creating shot volume strategy - his 'rebounds created' per hour via NaturalStatTrick.com went from 0.31 to 1.38 - but how much more potent does an extra rebound per 30 powerplays make your goal-scoring on the man-advantage?

Some of this is variance. You don't just post 1/5 of your shooting percentage year-over-year on merit (though being injured and trying to double your shots rate will certainly help) but what does the location say? Was he shooting from further out as well?

So it looks like the change wasn't a distance one but a degree one; Klefbom fired from everywhere up top and rotated to the left side often for same-side one-timers.

I noticed the centre-point shots, and I'm guessing all those left point releases had were aimed at a high slot tip.

It's easy to imagine a common response to what I'm writing in criticism of over-reliance on point releases is that I'm ignoring the danger that comes out of rebounds and other non-goal outcomes, but what I mean when I say point shots aren't dangerous is that they're not even dangerous when you include the rebounds you create or the tip opportunities.

That's to say, all of the more dangerous non-goal outcomes of releasing a puck off of the point happen more often and more consistently from a play that came from closer to the net.

By NaturalStatTrick's rebounds created, forwards with more than 100 minutes at 5-on-4 took 12854 shots, 7338 registered on goal, resulting in 978 rebounds.

Compare this to defencemen of the same TOI cutoff, who took 5008 shots, 2332 on goal, generating 352 rebounds.

So regular PP forwards take shots that are unblocked and hit the net on 57.1% of their attempts, 7.6% of their attempts generate rebounds and 13.3% of the SOG's do.

Comparatively, just 46.6% of defencemen shots go unblocked and force a save, 7.0% of their attempts generate rebounds and 15.0% of the SOG's do.

So, if it actually gets to the net there's a slight increase in the chance of a rebound, but once the low rate of attempt conversion is accounted for, you're no better off.

Considering how much less often these shots actually score, that leaves us with the conclusion that releasing plays from the point isn't exactly 'getting it to the net', because when your forward is shooting you're (slightly) more likely to get a rebound anyways.

The thing about this is, though. is a lot of the time I've heard and read traditional hockey mind's thoughts on it that it's a failure of puck-retrieval if you're losing ground in opportunity cost by opting to fire from the point. My response to this would be that, as a whole, the best puck-retrievers in the league's first powerplay units aren't far in net outcomes from the worst - the biggest factor is the bounce - because generally if you're on the top powerplay unit, you're a player with a good head on your shoulders, you work hard and you're smart. You can say on any given night a powerplay didn't work hard enough on puck retrieval, and it can be true. But when we're talking about pulling things back to the big picture, macro stuff over the whole season, I don't think you're making up the ground lost statistically and recovering pucks so much better than another team's 5 best offensive players to buck an NHL-wide trend.

Then, there's the disappearance of the point play among league-leading powerplays.

Here are the heatmaps for the top-5 5-on-4 GF/60 teams:

The theme? Green up high. Winnipeg's deviating a little, but we've talked about their options for puck movement and their elite shooting talent.

The Cutting Room Floor

- Starting at the beginning of the season is good to see what the system was fresh off the conveyor belt, especially when it comes to personnel.

- This was a critical point in the season - for both the unit and the team. Edmonton was -13 in all situations goal differential, and they had 5 5-on-4 goals while they best teams had 15. Having a top powerplay unit would have kept them afloat, much like Pittsburgh's unit saved their season.

- I've cut out most of the transitional play where convenient. As I've said earlier in the piece, the zone entries and setting up wasn't a problem for the team last year. This is a conclusion that's come intuitively, if they have a near-league leading shot attempts rate, they're probably gaining and keeping the zone pretty well. Especially to my point earlier about puck retrieval rates,

I don't think you can game your Corsi For rate by instantly shooting from anywhere without just losing the puck and having to re-enter, which in turn lowers your rate as you waste time getting back in shooting position.. - This is a lot of video to annotate for my purposes requiring another long-form piece to fully review, and I'd also like to share the raw-ish material so you can come to your own conclusions without me drawing all over it like I usually do.

Here's what we're looking for:

- Does the play end up going back to the point more often than necessary?

- Is the puck movement directly prior to the shot cross-ice?

- Were attempted cross-ice passes broken up at a rate that point plays were the only option?

- Is Letestu in close as he could be?

- Is the play going to the net to Milan Lucic, or through Milan Lucic, very often?

- Does Leon Draisaitl have a concrete role?

- Does Oscar Klefbom shoot often with other plays available?

From what I can gather, the dream play is to get 97 the puck up high while the whole team spreads out in something of a reverse umbrella, and then as he comes in down the wall the rest of the unit closes in too, before making a play to the goal line and back in front.

Something I notice is the amount of times the shot comes from the same side of the ice as the last puck-movement - meaning no one has to move, not the goalie nor the defenders. This in part addresses question #2.

Something I notice is the amount of times the shot comes from the same side of the ice as the last puck-movement - meaning no one has to move, not the goalie nor the defenders. This in part addresses question #2.

Speaking of the questions, #4's data and video both answer the question the same way. 55 is much further out than in 16-17, and it doesn't appear to have been forced by the opponent to be this way.

On the bright side, I don't think the lack of dangerous passes seems to be a result of the players not being skilled enough to complete them, but rather that they weren't being demanded by the system. This bodes well for next years' team.

In regards to Milan Lucic, it appears that plays through him switches from behind-the-net-to-front plays to high slot tips and deflections coming from the outside lanes in.

And on Klefbom, I wouldn't say that they're just funnelling attempts through him without thinking, but rather that the only pre-requisite for a satisfactory point shot was just a tiny-bit of puck movement like a pass from the half wall to the point. That's not nearly enough deception or movement.

You'll also notice Draisaitl's absence from the top unit from a coupe of these games. This is in addition to the different roles thrust upon him.

Conclusions

It's easy to look at last year's powerplay and say they weren't dangerous enough or didn't work hard enough.

It's also easy to say take less point shots and get plays from behind the net to the slot, or move the puck cross-ice more often.

A coaching staff would probably roll their eyes at me if I told them that, musing that misexecution can ruin their best laid plans.

The team wouldn't take any point shots at all if there was always an option to make a more dangerous play, right?

My answer is twofold. One, if the optimal scoring play is so often unable to be executed by two of the game's best playmakers, the plan might need revising, and two, if you're asking Oscar Klefbom to take 250 shots it seems it's not a big deal to release plays from the point.

The optimistic conclusion I have here, is from the answer to the following question, already put forth multiple times in this piece: are the players failing to engineer potent scoring opportunities, or are there not many in the blueprint?

It's a mix of both. The 'dream play' for this powerplay scheme was too unrealistic most of the time, so the team did indeed defer to the easier, safer(for their team as well as the opponent) play, but the raw amount of tries they gave to generate a surer goal was low enough that their percentage wouldn't be that of a unit we could expect continued failure from.

In short, given better tactics and a level of execution simply in line with the returning players' ability, one could expect a powerplay well away from the depths it sunk to last season.

This is, of course, a reasonable point of view even without having gone through the research I have, but the point of this blog is to drill down on the popular talking points among the media and the fanbase.

So when everyone says the Oilers powerplay can be expected to bounce back, I'll give that theory a pass.

(Though, speaking of the public discourse, I think we've also made the discovery that the Oilers powerplay was even worse than what's talked about, and much more perplexing than the more famous penalty-kill!)

Fin.